Having out-grown the space at Ascot House and with increasing parking problems, this was to be our last time there, after several years of delicious lunches. We thanked them warmly for having us.

In his talk, Paul took us through the glass making process and we were surprised to learn that the oldest found so far is a small glass bead from 3,500BCE. Flat glass for windows was more complex, and stained glass windows involved a Master Glazier, as designer who, once it was agreed with the donor, then passed his annotated design to his workers -a man in charge of lead, one glass maker and one painter of detail, faces etc. Paint for faces was made from iron oxide which unfortunately has deteriorated over time due to sunlight.

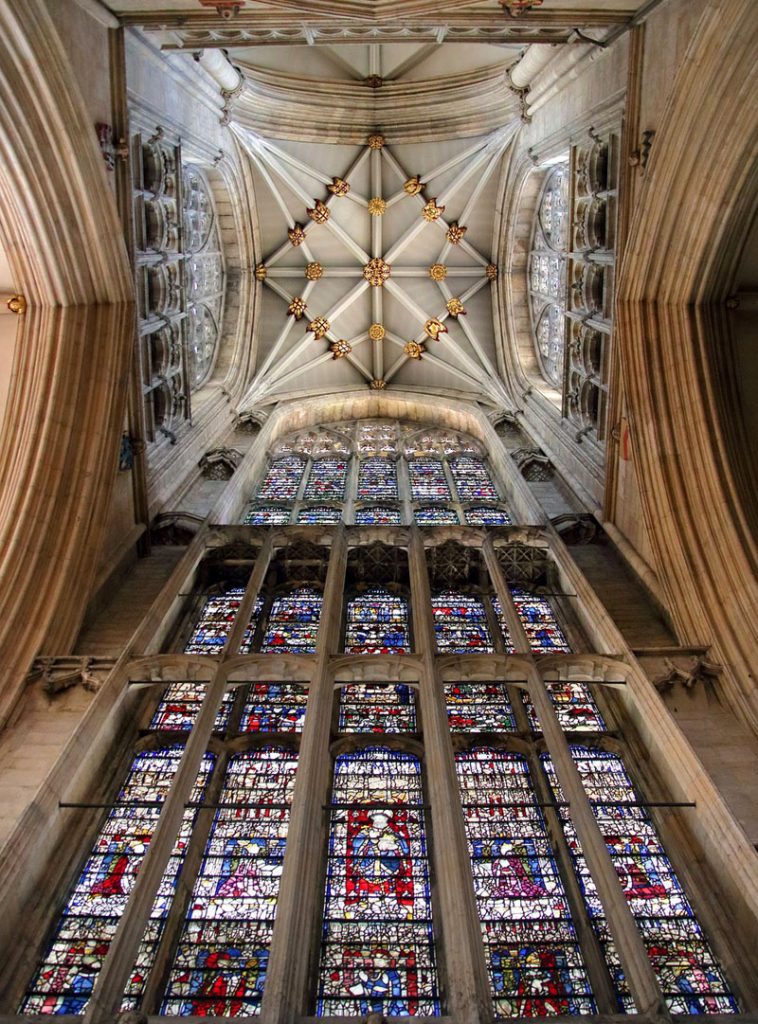

York Minster has some of the best medieval glass in Europe and the earliest panels date from 1170. Paul showed us some panels in great detail – which can only be seen from close up – not as the visitor sees from floor level as, for instance, the Five Sisters window is 53 ft high, – the largest expanse of grey or griselle glass in the world. The design for this window (in 1260) may have been influenced by Islamic Art following cultural exchange during the Crusades. By 1310 coloured panels had been re-introduced interspersed with the “grey” Islamic type patterns.

York Minster has some of the best medieval glass in Europe and the earliest panels date from 1170. Paul showed us some panels in great detail – which can only be seen from close up – not as the visitor sees from floor level as, for instance, the Five Sisters window is 53 ft high, – the largest expanse of grey or griselle glass in the world. The design for this window (in 1260) may have been influenced by Islamic Art following cultural exchange during the Crusades. By 1310 coloured panels had been re-introduced interspersed with the “grey” Islamic type patterns.

Bell founder, Richard Tunnock, was unashamedly self promoting when paying for his window and an unknown donor had a jibe at the priests and doctors in York with a “monkey margin” to the Pilgrimage window in the Nave.

The costs of the windows were astounding. William Melton paid £66 for the “Heart of Yorkshire” window in 1339, and for the Great East Window (which, being the size of a tennis court, is the largest Medieval glass window in Britain). John Thornton of Coventry was paid £56 for his three years’ work of 311 panels. This has recently been completely restored at a cost of £11.5 million and took ten years. It tells the story from Creation, and the lower panels show the End of the World, as the Medieval mind was fascinated by the stories in the Book of Revelation. Little snippets about St William’s shrine, and photos of the “information” or graffiti with signatures left by earlier craftsmen made this a most interesting talk, which I for one thoroughly enjoyed.

Jan Jauncey